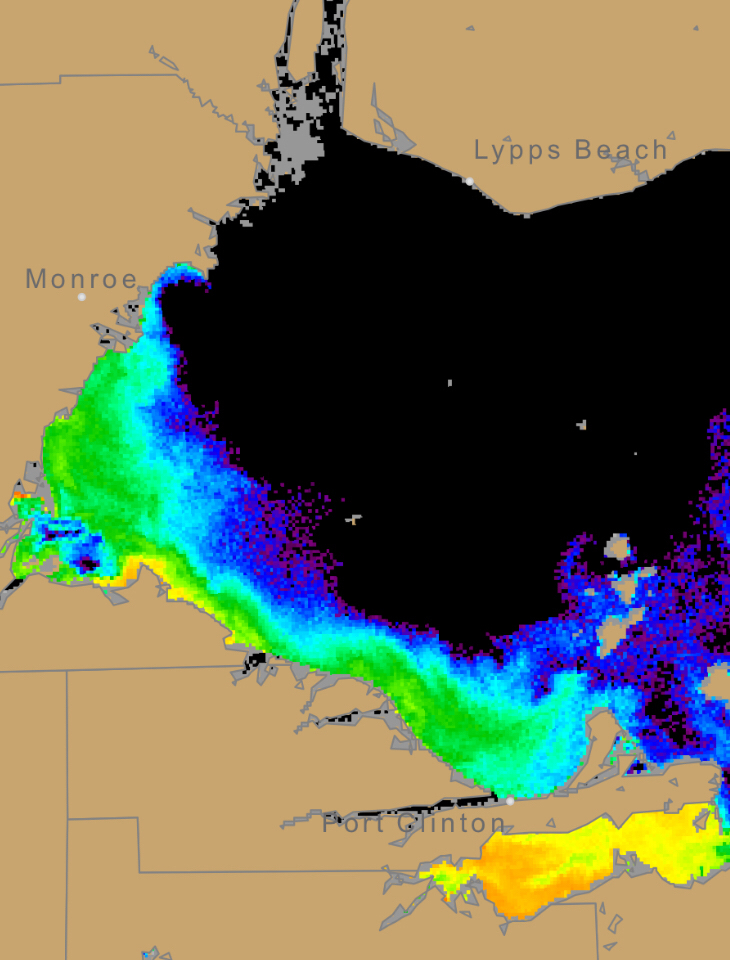

In late July and early September, during the peak of the 2018 harmful algal bloom in the Western Basin of Lake Erie, NOAA GLERL, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS), NOAA Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) and CIGLR researchers teamed up with a group of scientists and engineers from the Monterey Bay Research Institute (MBARI). Their mission: to test how well a third-generation environmental sample processor (3GESP), mounted inside a long-range autonomous underwater vehicle (LRAUV), can track and analyze toxic algae in the Western Basin of Lake Erie. You can read more about the purpose of this project in this great news story by MBARI’s Kim Fulton-Bennett.

Below is a photo story showing all (well, much) of the hard work that went into this test deployment.

First, the new gear had to be shipped from California to the GLERL laboratory in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

On the truck and heading to Michigan!

Ready to go.

It’s load out day!

The inside of the 3G ESP has a lot of moving parts. Since this is the first time the team is testing it in freshwater, before it can go out, everything needs to be fine-tuned to work in a variety of conditions in Lake Erie (more on that later.)

So. Many. Moving. Parts.

Running a test sample.

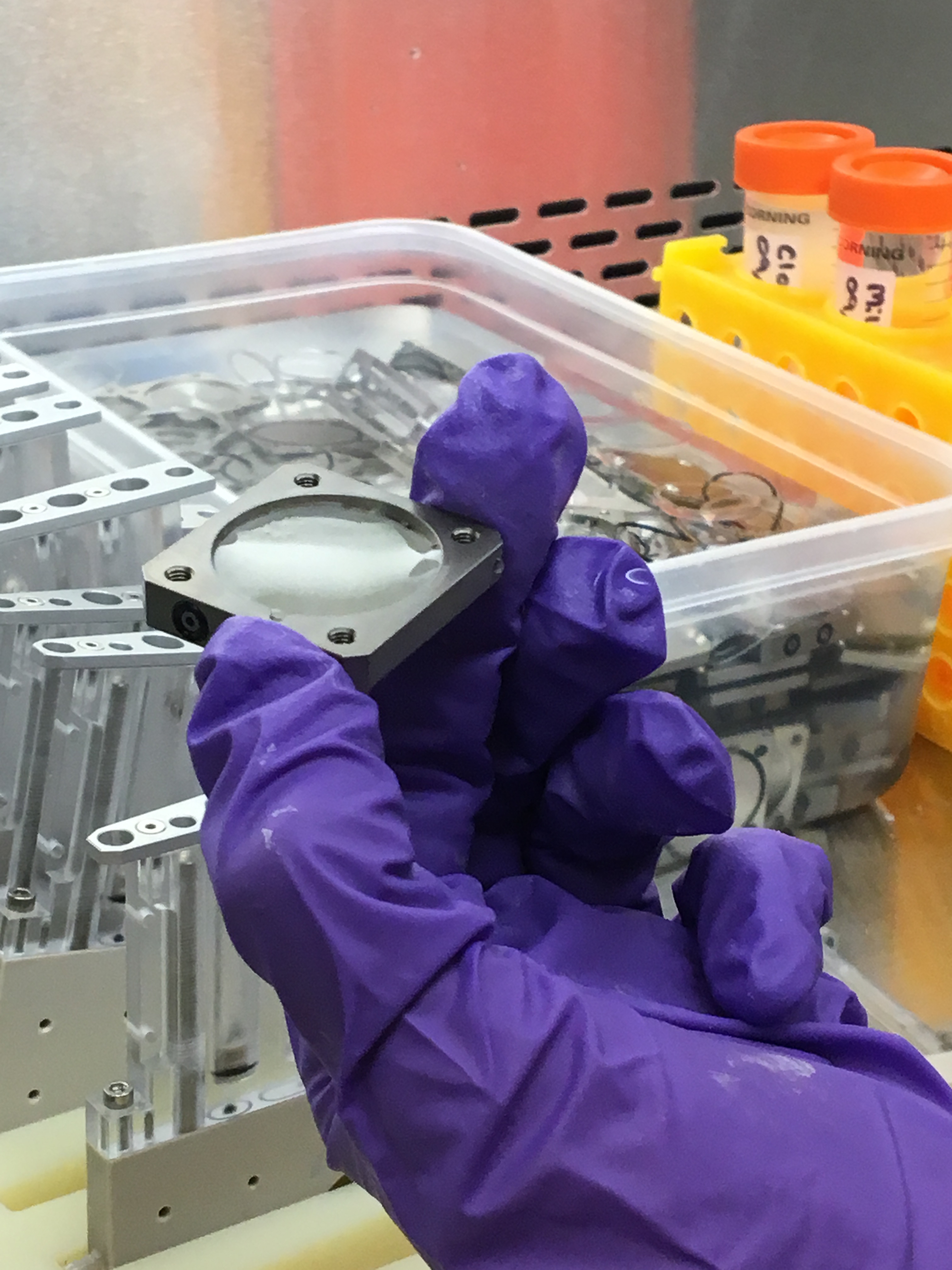

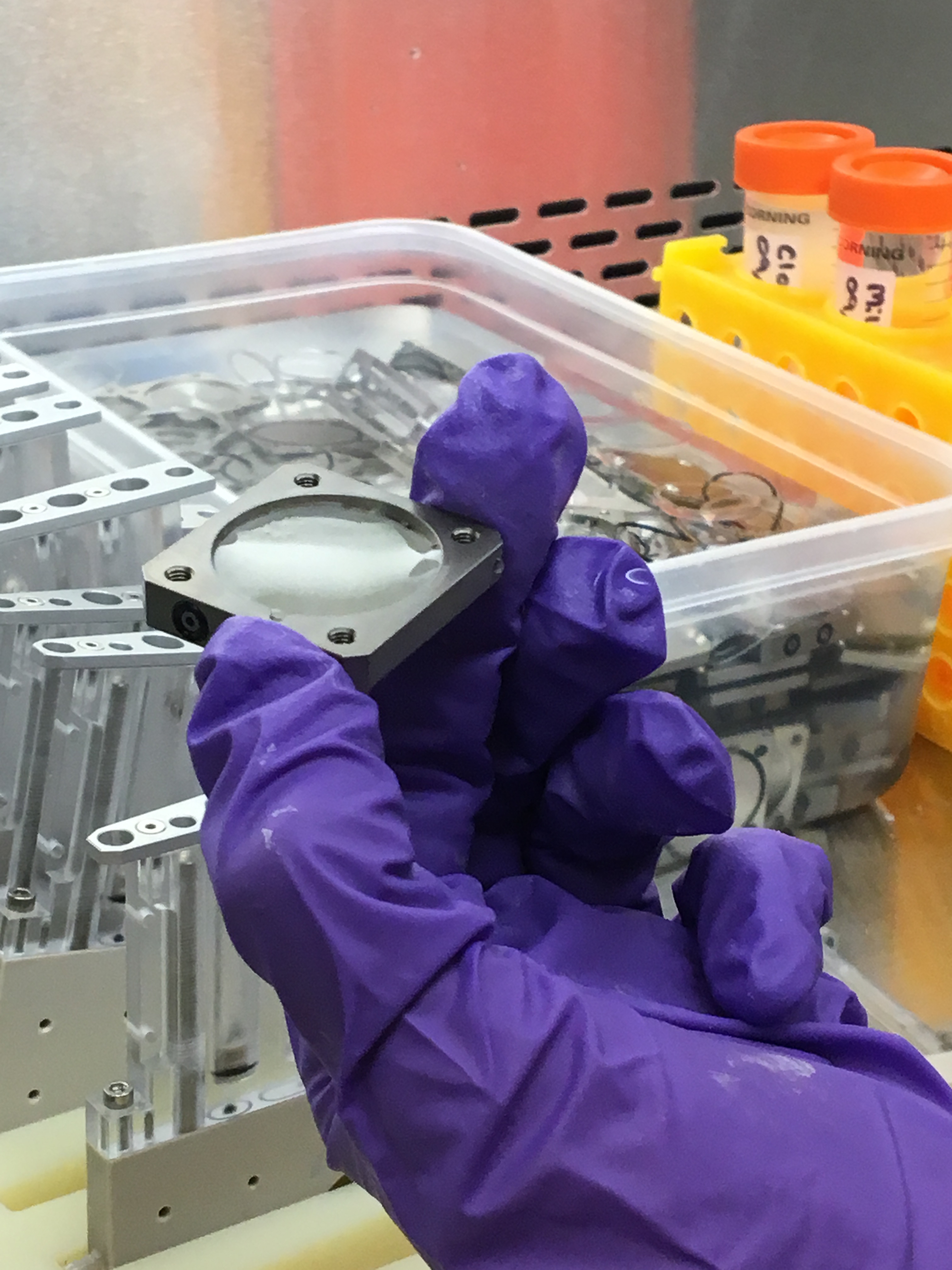

Cartridges that hold the water sample for both real-time processing, as well as an archive sample for further analysis back in the lab.

The propeller end of the long-range AUV in which the 3GESP will be housed.

More testing and tweaking.

The “guts” of the 3GESP prior to inserting the cartridges.

Once everything is in working order, the 3GESP gets inserted into an LRAUV or long-range autonomous underwater vehicle (the torpedo-looking thing). This gives the 3GESP the ability to move around in the water all by itself once researchers have set parameters for it. The team has named this particular vehicle, Makai, which is Hawaiian for “toward or by the sea.” Seems appropriate! That’s Brian Kieft, MBARI software engineer, on the right. He plays a crucial role in making sure Makai does her job.

All hands on deck for a few more tweaks.

Once everything is installed tightly, helium is added into the canister to check for leaks. CIGLR engineer, Russ Miller, is working with Jim to fill it up.

Now, the team is ready to head out to Lake Erie. Here’s where things start to get exciting!

A kayak? What do we need that for? You’ll see.

Loading the Makai into the van.

Heading to Toledo Beach Marina in La Salle, Michigan .

Before the team sets Makai free to track the algal bloom in the Western Basin of Lake Erie, they must first check her ballast and trim. This is especially important for such a shallow lake (relative to where the team has been testing this technology in the deep canyons of of Monterey Bay off the coast of California.)

Brian has to do all of the hard work.

Because, science.

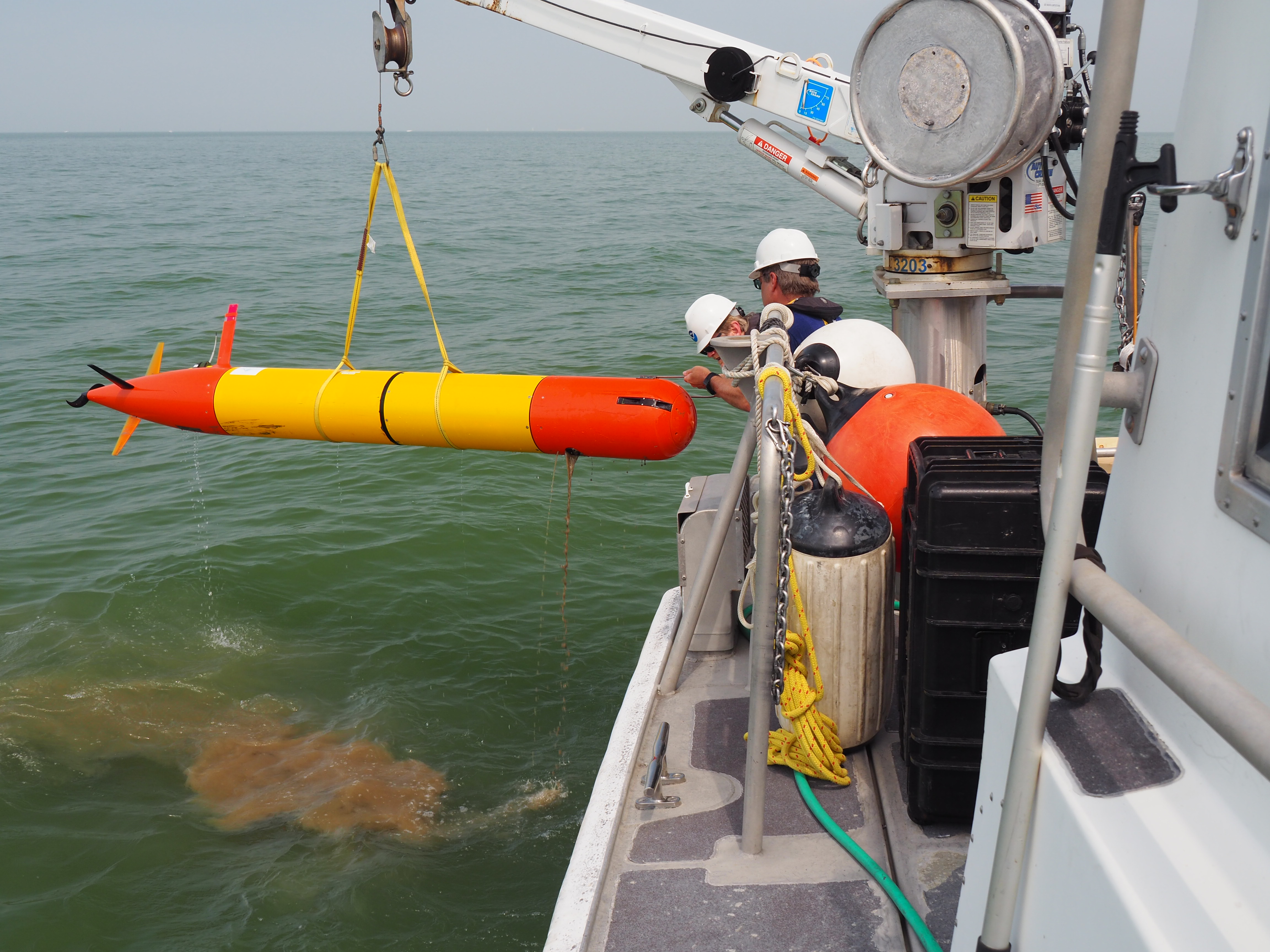

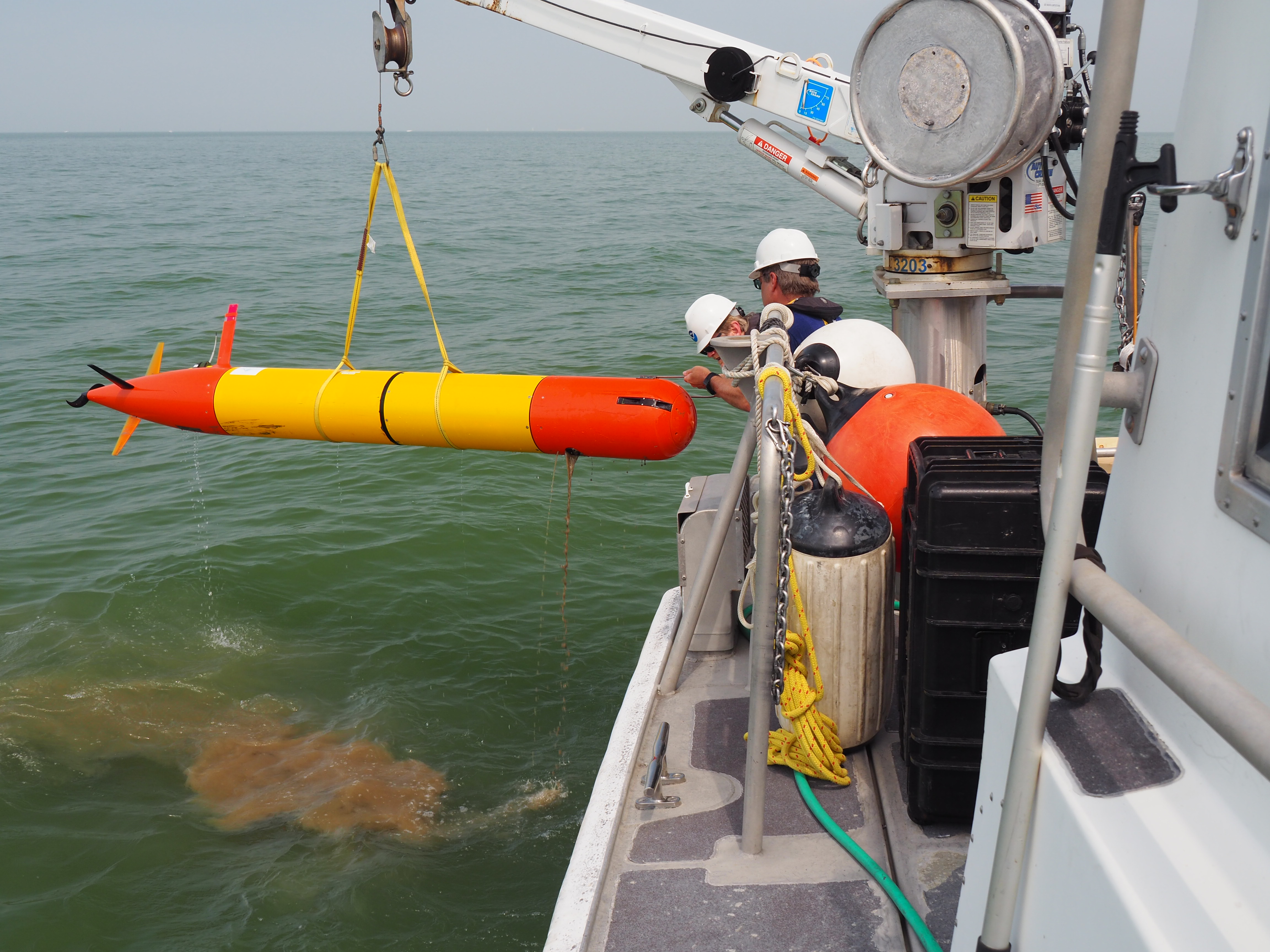

Time to load Makai onto the NOAA vessel, which is stationed in La Salle, Michigan. Captain Kent Baker, a contractor with NOAA, is in the background operating the crane. Kent takes NOAA and CIGLR researchers and technicians out to bi-weekly sampling stations, helps deploy buoys and other instrumentation, and is at the ready for pretty much anything that needs to happen in Lake Erie.

Once she’s all settled onto the boat, the team takes Makai to the first deployment location.

Look closely and you’ll see Makai off on her way!

Makai and the team spent nearly two weeks tracking, sampling, adjusting, and learning about using this technology to track algal toxins in Lake Erie.

Then, they would determine how many samples to take, and program her to go to specific waypoints.

Remember when we said this Lake Erie mission will be different than the ones the team has performed in Monterey Bay? Well, here’s one example of how.

After a few hours of no communication, and a little hunting, this is how the team found Makai. Two problems here: One, with the propellor up and the nose down, Makai cannot transmit data, including her location, as the transmitter only works above water. And, two, well . . .

The reason she was nose down in the first place is because Lake Erie is pretty shallow, and she’d taken on quite a bit of mud.

Once she was all cleaned up, the team set Makai out again to complete the rest of her mission.

Once the deployment was over, the research didn’t stop there.

Archive samples were taken so that folks back in the lab could further analyze them.

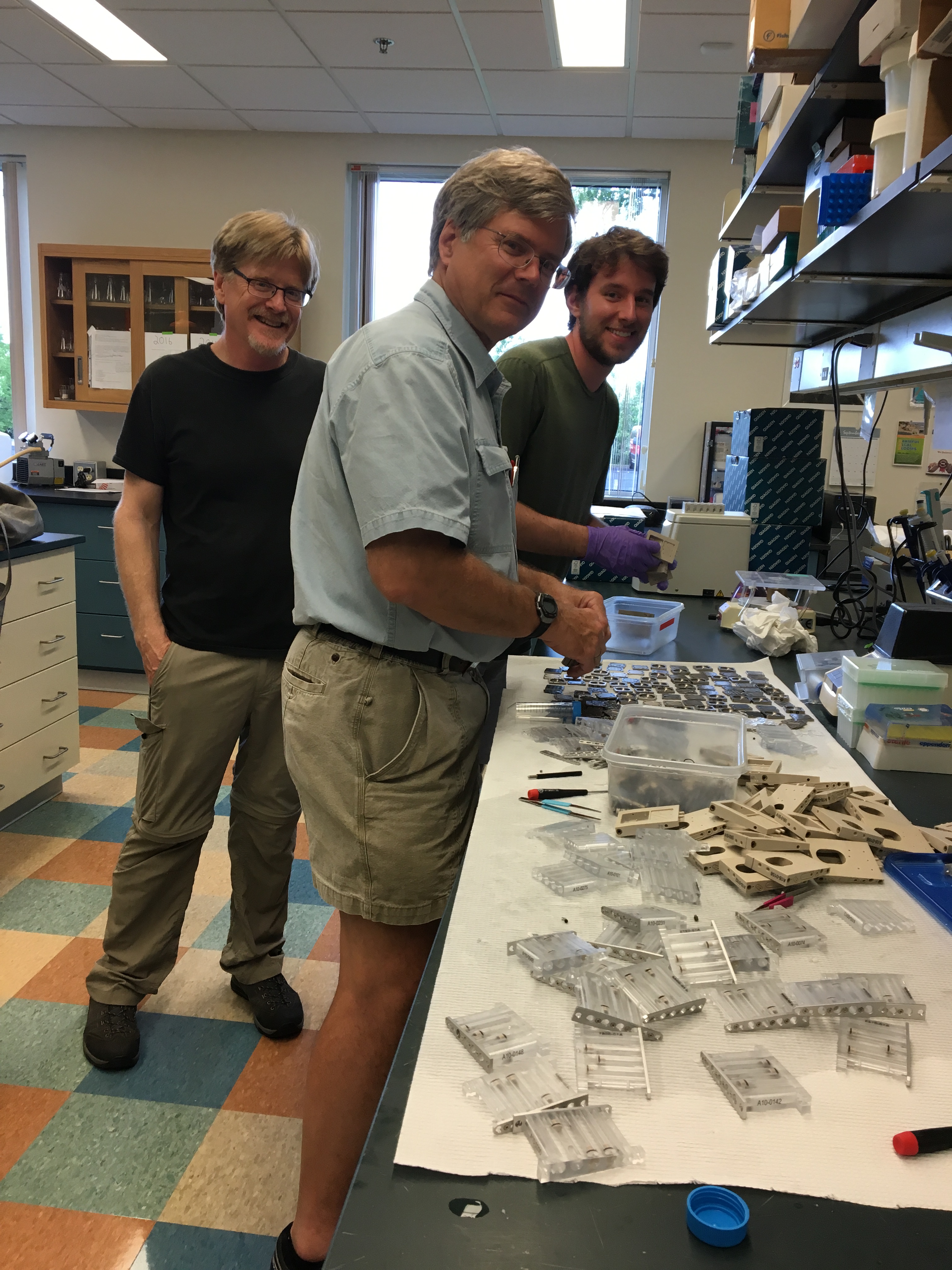

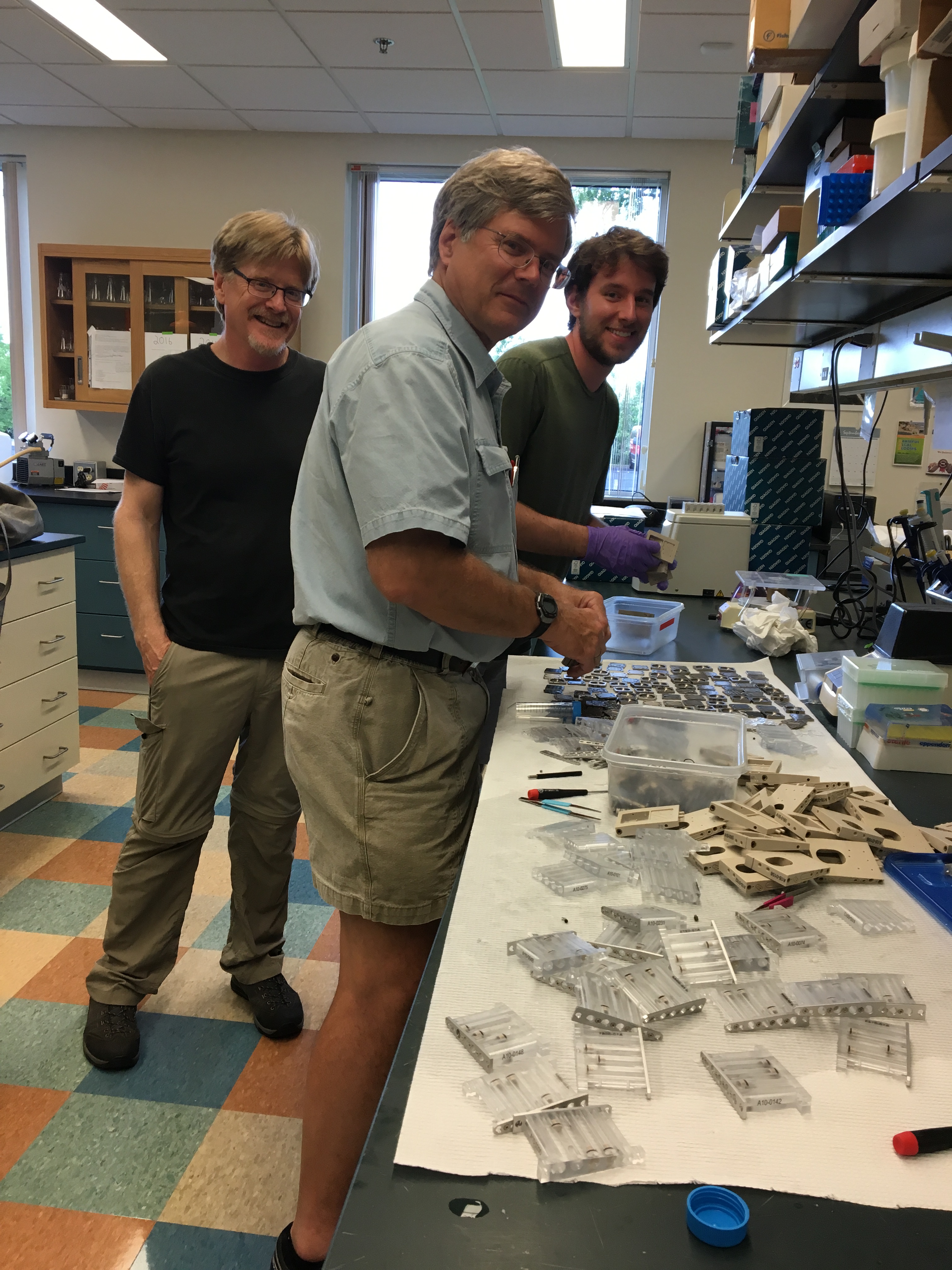

Here’s GLERL’s Observing Systems and Advanced Technology (OSAT) branch chief, Steve Ruberg (left), along with Paul Den Uyl, a researcher with CIGLR, helping Bill extract the sample filters from the cartridges.

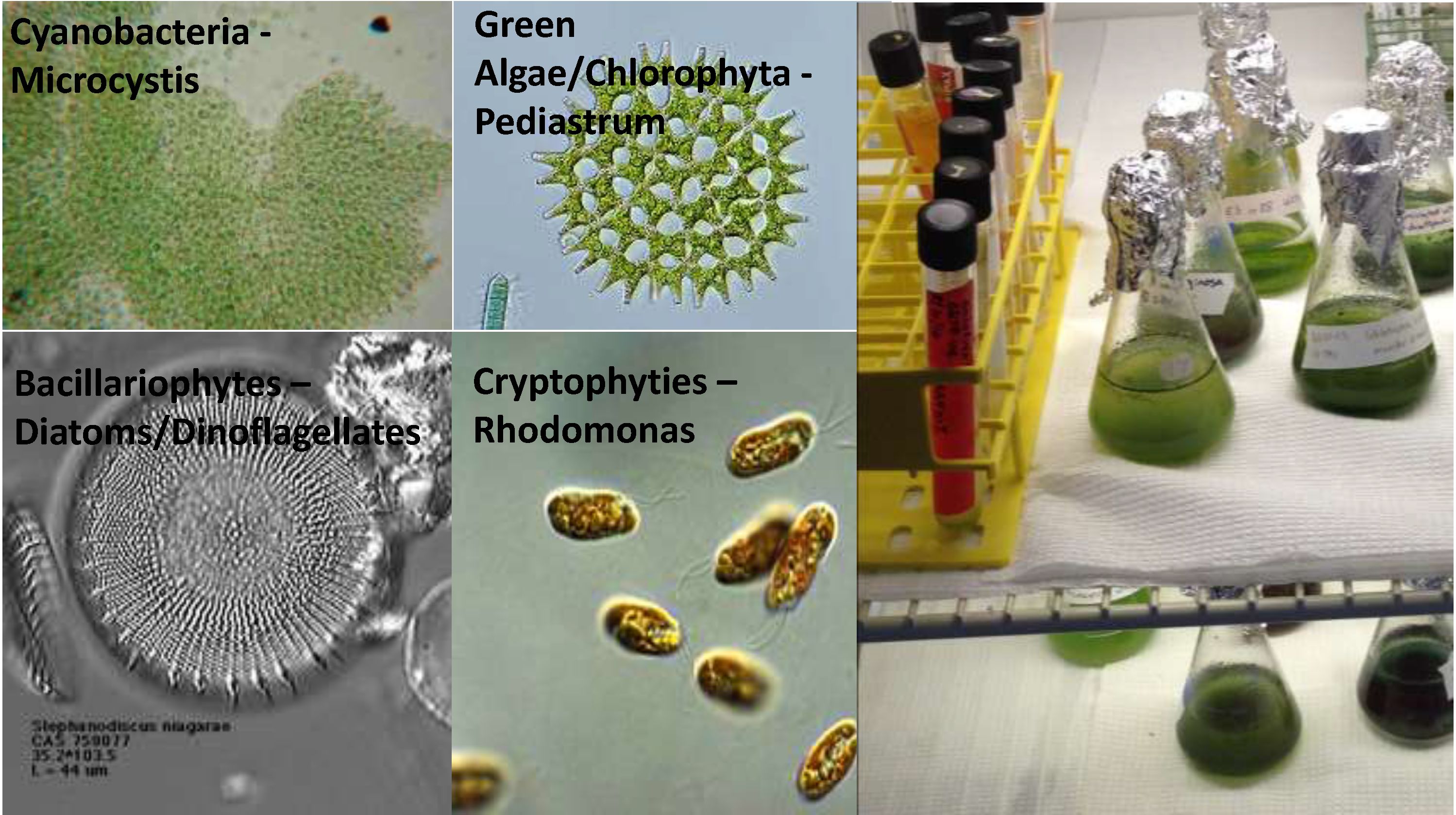

The filters are being collected for analysis of DNA. The DNA will be extracted from each filter and analyzed. We’re looking at absolute quantity of known microcystin producing toxin genes in samples collected, information on bacterial community composition, and information on eukaryotic organism community composition. The samples will also analyzed through shotgun sequencing. This is where all of the genes in the sample are turned into human readable information and can be combined to make what can be thought of as an organism’s genetic instruction guide (what genes it has). This information will be very helpful in better understanding what causes the algae to be toxic (not all algae is toxic).

Last week, GLERL scientist

Last week, GLERL scientist  The sampling and research we’re doing in Lake Okeechobeeo helps us get a better understanding of the environmental drivers behind changes in bloom toxicity—a main focus of the research we’re doing within our

The sampling and research we’re doing in Lake Okeechobeeo helps us get a better understanding of the environmental drivers behind changes in bloom toxicity—a main focus of the research we’re doing within our