It’s nearly winter here in the Great Lakes—our buoys are in the warehouse, our boats are making their way onto dry land, and folks in the lab are working hard to assess observed data, experiments, and other results from this field season.

This is a retrospective animation showing the predicted surface chlorophyll concentrations estimated by the Experimental Lake Erie HAB Tracker model during the 2018 season. Surface chlorophyll concentrations are an indicator of the likely presence of HABs. For more information about how the HAB Tracker forecast model is produced and can be interpreted, visit our About the HAB Tracker webpage.

The harmful algal bloom (HAB) season is also long over in the region. The final Lake Erie HAB Bulletin was sent out on Oct. 11, as the Microcystis had declined in satellite imagery and toxins decreased to low detection limits in samples. In the seasonal assessment, sent out by NOAA’s Centers for Coastal Ocean Science on Oct. 26, it was determined that the season saw a relatively mild bloom—despite its early arrival in the lake—and the bloom’s severity was significantly less than that which was predicted earlier in the season. These bulletins and outlooks are compiled using several models. Over the winter, the teams working on the models take what they learn from the previous season, and update their models for future use.

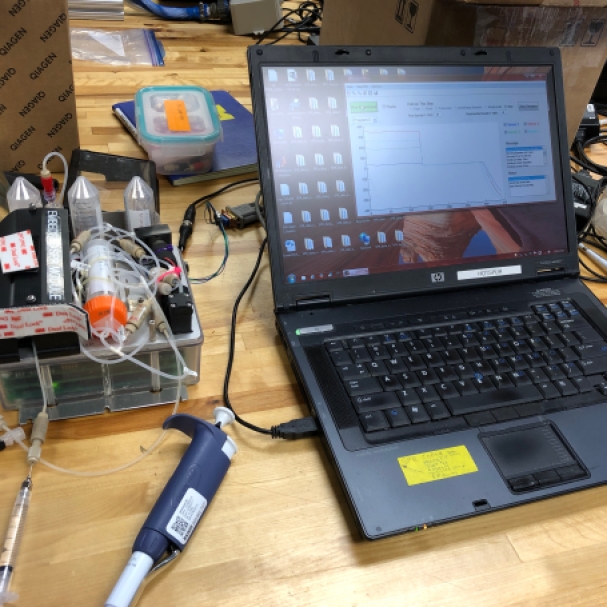

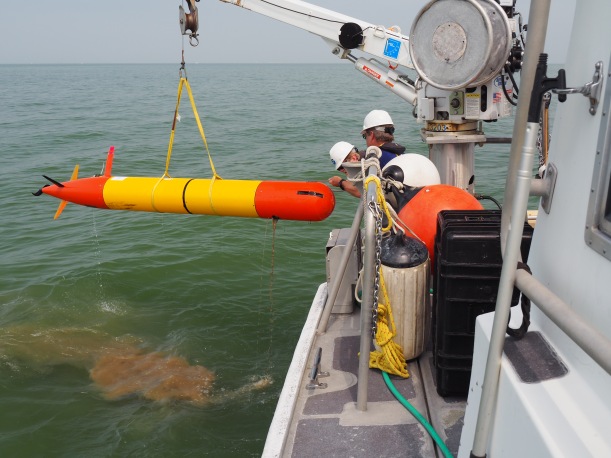

Back in the lab, the HABs team—researchers from both GLERL and the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research (CIGLR)—will spend the winter analyzing data they collected through a variety of observing systems. This summer was packed with the use of new observing technologies, like hyperspectral cameras and the Environmental Sample Processor (in case you missed it, check out this fun photo story of the experimental deployment of a 3rd generation ESP). In addition, GLERL and CIGLR staff maintained a weekly sampling program program, from which scientists are analyzing and archiving samples and conducting experiments.

Aerial photograph of the harmful algal bloom in Western Basin of Lake Erie on July 2, 2018, (Photo Credit: Aerial Associates Photography, Inc. by Zachary Haslick). Pilots from Aerodata have been flying over Lake Erie this summer to map out the general scope of the algal blooms. In addition to these amazing photos, during the flyovers, additional images are taken by a hyperspectral imager (mounted on the back of the aircraft) to improve our understanding of how to map and detect HABs. The lead researcher for this project is Dr. Andrea VanderWoude, a NOAA contractor and remote sensing specialist with Cherokee Nation Businesses. For more images, check out our album on Flickr.

This lab work is super important for understanding the drivers of toxic algae in the Great Lakes. For instance, in a new study released this month, researchers looking at samples from previous years found that “ . . . the initial buildup of blooms can happen at a much higher rate and over a larger spatial extent than would otherwise be possible, due to the broad presence of viable cells in sediments throughout the lake,” according to the lead author Christine Kitchens, a research technician at CIGLR, who works here in the GLERL lab. This type of new information can be incorporated into the models used to make the annual bloom forecasts.

As you can see, our work doesn’t end when the field season is over. In spring 2019, when the boats and buoys are back in the water and samples are being drawn from the lakes, researchers will already have a jump on their work, having spent the winter months analyzing previous years, preparing, and applying what they’ve learned to the latest version of the Experimental HAB Tracker, advanced observing technologies, and cutting-edge research on harmful algal blooms in the Great Lakes.